The Traveling Breastplate | ཐུགས་གསལ་མེ་ལོང་ཐུགས་ཀྱི་མེ་ལོ

- Dolma Tenzing

- Mar 24, 2023

- 16 min read

An Object Biography on the Nechung Oracle's Breastplate

Mirrors are often perceived as gateways to another realm, a literal and spiritual reflection of the self, an image of perceived reality. In the Buddhist context, mirrors are known to be a gift from the goddess of light, Prabhavati, to the Shakyamuni Buddha. As political and diplomatic communication from surrounding empires began to rise, Tibet fell into the hands of British invasion, leaving thousands of precious objects and teachings scattered across the globe. One of these treasured items is the Nechung Oracle's Breastplate obtained during an invasion through southern Tibet. This biography aims to highlight the Nechung Oracle's breastplate, presented by Dr.Emma Martin, and connect its relevance to the political environment of the early 20th century during the British invasion of Tibet. The story following the Nechung Oracle's breastplate illustrates the significance of religious figures and their absence in Tibetan society, the impacts of colonization, and its portrayal of Tibet thereafter.

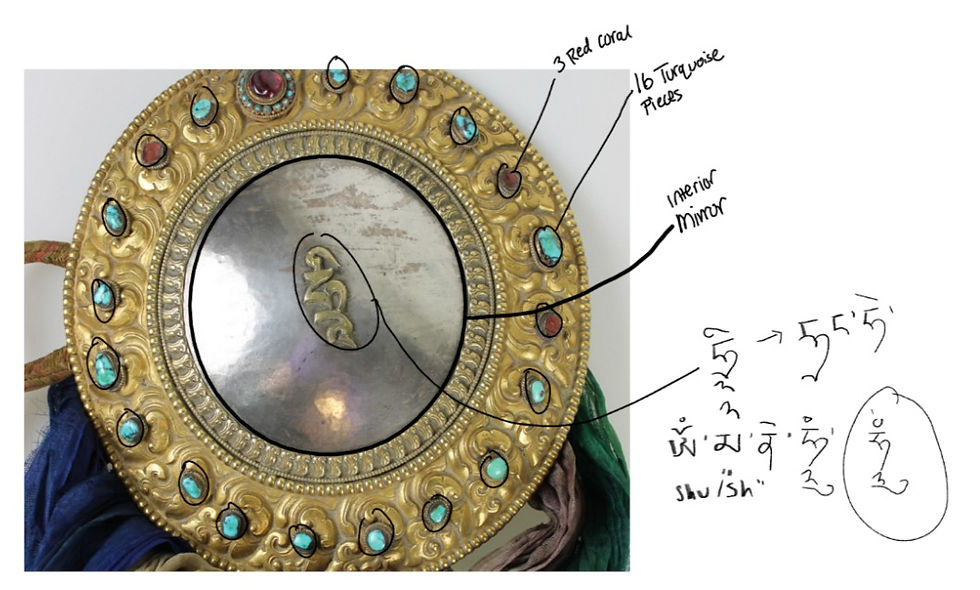

The object of focus is the Nechung Oracle Breastplate held in the collection of National Museums Liverpool. The following paragraph will introduce the object, its objective appearance, and its standing within the museum. According to an object descriptor posted by Dr.Emma Martin, a lecturer in Museology specializing in Tibetan materiality and South Asian collections curation, the object is a part of a greater collection known as "Provenance Research”. The Oracle Breastplate Mirror (ཐུགས་གསལ་མེ་ལོང་ཐུགས་ཀྱི་མེ་ལོ) is noted as created before 1904 in Lhasa. Based on online images(noted in Figures 1 and 2), the most pertinent aspect of this breastplate is its centric mirror that reflects the light of the museum's camera. In the middle of the breastplate, a Sanskrit mantra inscribed with the protectorate emanation of Pehar, Dorje Drakden, can be viewed. On the mirror's contour, sixteen nodes of turquoise, three nodes of coral, and a single ruby are adorned along the gilt copper alloy disc. Blue, yellow, white, green, and washed-out red silk streamers are attached to the base of the disc, along with an attachment for the neck during ceremonial use.

According to accounts by the current Nechung, Venerable Thupten Ngodup, the experience of going into a trance requires a considerable amount of bodily regulation in food consumption, ensuring that the channels are clean. Once cleared, the human form can wear the "Royal Robes." Venerable Thupten Ngodup shared in a personal interview that the regalia was offered to the Dharma protector by the regent Desi Sangye Gyatso at the time of the Great Fifth Dalai Lama. They are thus called "the royal robes of a king." In addition to the breastplate, the hat weighs up to fifteen kilos due to the amount of gold used to embellish it. New sets of attire were re-created, and one was gifted to a museum in Geneva, Switzerland, for an exhibit highlighting various oracles worldwide. While the significance of the mirror to the oracle is never explicitly stated, Venerable Thupten Ngodup recounts the experience of physical body pain felt in the chest and the head. Based on accounts and research published in the Columbia Tibetan Studies blog, mirrors (མེ་ལོང་) represent divinatory power. Perhaps the mirror's vicinity to the chest and the heart serves as a symbolic representation of the body as a vessel for the medium, serving a spiritual purpose for the physical experience of trance through the attire. A link to his interview can be found in Figure 3.

The Liverpool Museum notes the collector to be John Claude White and the mirror’s retrieval to be sometime between 1904-1908. The materials used to create the object include textile silk; silk yarn; glass; copper alloy; silver; metal gilt; turquoise; and wax. Turquoise is also termed the Stone of the Sky, giving auspicious items such as this breastplate the nature of spiritual wardship. The only recorded account of travel for this object is tied through a credit line that notes a purchase from the collections of Norwich Castle Museum in 1956, making its way into permanent collections at the National Museum. The journey of this object is an important reflection of Tibet's shifting political and religious atmosphere during the early twentieth century, particularly through the foreign relationships Tibet encountered with the British invasion. However, before understanding the coeval presence of this object during the twentieth century, the historical background of the Nechung and its role in the rising Gelukpa tradition of the Dalai Lamas is an important facet of deconstructing the locality of this object in Liverpool's collection.

The Nechung Oracle and its origins cast a wide net when deciphering its exact inception into Tibetan Buddhism. For this object biography, I will reference Dr.Christian Bell's work titled "The Dalai Lama and the Nechung Oracle '' and highlight a few essential characteristics of the Nechung. In chapter one of Bell's work, the Nechung is introduced as Pehar, a protectorate deity whose nature was defined by its various emanations. Due to Pehar's varying lifetimes, an effort to describe Pehar's narrative allowed authors and storytellers to highlight certain elements over others. As shared by Bell,

"This concept is so ingrained in the Tibetan image that it is a non-issue so much that when I have brought up Pehar's different forms to various Tibetan monks and laymen, they all invariably said the same thing: deities change forms like we change clothes. Nevertheless, these diverse and sometimes contradictory texts provide an opportunity to draw out a bricolage that appeals to the narrative goals of particular individuals or institutions''

The expansive mythos of Pehar is a potential byproduct of his multi-sect history, traveling between the Nyingma, Sakya, and Geluk schools as an opportunity for followers to utilize Pehar's power and representation for their schools. Despite Pehar's Nyingma origins as dated in twelfth-century treasure texts and wide-ranging illustrations and characteristics into other sects, this is an important indication of how spiritual deities, specifically Pehar, were viewed with malleability and power by the Tibetans up to the seventeenth century. The significance of Pehar to the Fifth Dalai Lama is an important facet of Tibet's political history because the establishment of the Nechung as the state-sanctioned deity and the Dalai Lama's spiritual affiliation influenced the presiding government, serving as an oracle to the state. At the time, His Holiness was an active advocator for rites, rituals, and ceremonial offerings in addition to his secular and religious leaders during his reign. The Nechung Oracle reflected the importance of protection for the Gelugpa regency as the Gelugpa tradition began to reflect a shift in the utilization and codification of spiritual ritualization in political and social affairs. The transformation of the Nechung into a state oracle gives rise to the modern placement of the Nechung as a minister within the Tibetan government, symbolically bordering the socio-political power of the Gelugpa school. In addition to its political influence, the Fifth Dalai Lama sought this as an opportunity to forge a synthesis between the Geluk and Nyingma schools. Phuntsog Wangyal references the Dalai Lama's role in government as the dual system of government under the Gyalwa Rinpoche, which was divided among both Gelugpa and Nyingma monks and laypeople.

"The term 'Ch'o-so nyi-dan' appeared for the first time in the seventeenth century when the Fifth Dalai Lama reorganized the government of Tibet… She's-so nyi-dan is dual not in the sense that there are two parallel and separate governments functioning simultaneously, but in the sense that the government has a double personality."

There is a clear distinction in the importance of Pehar's presence within early Tibet, which later develops Nechung into a cohesive and active deity in the lives of the following Dalai Lamas. In the seventeenth century, Pehar's establishment as Nechung made way for the creation of the Nechung Monastery located in Lhasa, where the Thirteenth Dalai lama became one of the most significant patrons of the monastery. According to Christian Bell, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama accounted for about 115 monks within the Nechung monastery, making it a significant space for its religious purposes. Just at the turn of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama's reign, the Nechung Oracle was invoked by the Tibetan Government and urged the Dalai Lama to flee to Mongolia in 1904. This was the same year that the British Expedition to Tibet by Sir Francis Younghusband began.

The following paragraph will highlight the role and significance of the Nechung's absence in the monastery and its impression upon British explorers at the time. In Dr.Emma Martin's descriptor of the breastplate and its retrieval, she relays the historical accounts written by Perceval Landon in his book, "The Opening of Tibet." In the absence of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama and the Nechung, the Nechung's regalia, including the breastplate, was placed on his throne. These adorned pieces were meant to represent a 'placeholder' for the Oracle in his physical absence, leaving a symbolic notion of the power and reverence the Nechung held.Various images from this expedition provided by Dr.Emma Martin can be referenced in figures 4 and 5. Along with Perceval Landon, John Claude White, the Joint Commissioner of the 'Mission to Tibet,' pursued the Oracle's throne to obtain one of the auspicious objects. It is important to note that in Dr.Emma Martin's account, she restoratively highlights the undermining power dynamic that this era of British colonialism had over these monastic institutions, primarily using the guise of violence to coerce the retrieval of this breastplate. While historical accounts by the explorers do not share this perspective, it is important to acknowledge how unequal exchange is often a byproduct of a trade by duress from the British. In the words of Perceval Landon,

"Mr.Claude White was lucky enough to persuade the monks to sell him the little circular shield I have described. They said they could easily replace it, and I am inclined to think they made more than a trifle out of the transaction."

Whether collectors acknowledged this or not, the underlying role that the British played in the absence of the Nechung and the Thirteenth Dalai Lama at this time was a pivotal shift in the political nature of Tibet. Following the absence of the Dalai Lama, the Qing court withdrew its recognition of the Dalai Lama. They abolished his titles for the time being, allowing significant events such as the Convention of Lhasa to occur in the presence of the Amban and other foreign representatives. The significant pressure received by the Ganden Phodrang from the Qing and British empires placed a critical lens on the recognition of Tibet as an autonomous and powerful state. As the new world began to shift into expanding its dominance, the once-isolated Tibet could no longer rely on its border protections. In the final political testament of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, his contemplative ideas on the future of Tibet remains an important marker for Tibetan society.

"The present is the time of the Five Kinds of Degeneration in all countries…They seized and taken away all the sacred objects from the monasteries. They have made monks work as soldiers. They have broken religion, so that not even the name of it remains…It may happen here in the centre of Tibet the Religion and the secular administration may be attacked both from the outside and from the inside…The officers of the state, ecclesiastical and secular, will find their lands seized and their property confiscated…the days and nights will drag on slowly in suffering"

The reflections of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama are a notable protraction for the following century. How the British continued to collect and disperse important religious objects throughout the world after Tibet's invasion is a stark reminder of the impacts that colonialism has today.

Coming back to the object of focus, Nechung's Breastplate, the story of how this object traveled throughout time can be told through the numbers ascribed to its holy body. In museum categorization, numbers are used to identify objects. The accession number is 56.27.218, indicating that Liverpool Museum retrieved the object in 1956. A reference to this number is found in Figures 6. During the era of colonial collections in the early 20th century, museums' abilities to maintain documentation of an object's traveling timeline streamed into the hands of staff members who obtained objects frequently through donations, gifts, or by purchases. Once Claude White returned to Britain in 1908, he sent his collection to the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery in 1928, and in 1956 he sold the collection to the Liverpool Museum. Dr. Martin notes that the museum's staff incorrectly labeled the breastplate as "Machung Mon. Lhasa Tibet 1904. J. C. White. Lama’s Breastplate”. It was only when Claude White's granddaughter found a reference to the original breastplate in her book collections that the breastplate was restored to its original name. Following visits to the Nechung Monastery were able to provide various images of the monastic institution as well as color print photographs obtained by Hugh Richardson in the late 1930s-1940. Figures 7 and 7.1 provide images from the British Museum, titled the “Tibet Album, British Photography from 1920-1950”, with support to access by Chukyi Kyaping

Following the journey of this 44.29in x 7.2in object throughout time, the story of this object retells a powerful story of the Nechung Oracle and its origins while also serving as a reminder of its absence throughout time. Utilizing Dr.Emma Martin's object lessons from Tibet & The Himalayas and the historical contextualization of Dr.Christopher Bell, this object biography relays the significance of the Nechung oracle during the early 20th century during British invasion. Reflecting on the current state of the Nechung today, the breastplate used today maintains a mirror in the center with larger adornments of stones around the center. It reflects the same gold grandeur in photographs as it did in the 20th century. Despite the plate's absence in 1904, the rituals and communal significance of the Nechung have remained. Holding on to the intimate and complex nature of Tibetan craft, the continuation of the Nechung Oracle’s rituals continues to solidify the strength of the Tibetan government and the Tibetan people.

Note: Figures 8, 8.1, 8.2, 9, 9.1,9.2, 10,10.1,10.2 are extra images not referenced in the essay above.

Figure 1.

The Nechung’s Breastplate as referenced with Dr.Emma Martin’s publication on the Object lessons from Tibet Blog. As noted above, the object is adorned with multiple precious stones as well as the silk streamers that drape below. The sign for Dorje Drakden, the protectorate deity, is inscribed in the middle of the plate. In literal translation, the syllable Hri is written. This term is typically used in mantras, however, the Nechung invocation rituals and travel involve praying to the five buddha families and other deities. At most, the mantra could have been inscribed on the mirror because of its auspicious significance.

Martin, Emma. 2020. “August 1904: Nechung Oracle’s Breastplate.” May 12, 2020, https://objectlessonsfromtibetblog.wordpress.com/2020/05/12/

Figure 2.

A close-up image of the breastplate. A few areas of focus include the 16 Turquoise pieces and the 3 coral stones attached to the mirror. Turquoise is a treasured part of the Tibetan diaspora, locally sourced from its natural environment, the formation of its color comes from the percolation of groundwater and the presence of copper. The interplay between the natural environment and its application in adornment can be a representation of the relationship between the spiritual deity and the natural world. It is important to note that Turquoise and other stones are not reserved just for the special deities, but for lay people, the ability to own and wear the stones serves as a social marker of one’s personal wealth.

Martin, Emma. 2020. “August 1904: Nechung Oracle’s Breastplate.” May 12, 2020, https://objectlessonsfromtibetblog.wordpress.com/2020/05/12/ august-1904-nechung-oracles-breastplate

Figure 3.

This source is a short interview conducted by the educational site, StudyBuddhism. This interview was conducted with the Venerable Thupten Ngodup where he described the process and invocation of going into trance. He makes note of the attire worn during trance, which is where references to the Breastplate are mentioned in the biography above. The relationship of the item to the body holds value to the ceremony. What can be observed in addition to this physical attire is the similarity it shares to artistic depictions in monastic institutions, further images will be provided below.

Study Buddhism, “Preparing to Go into a Trance| Ven. Thupten Ngodup, the Nechung Medium, 3:49, April 30, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lN3NmaWjIPM

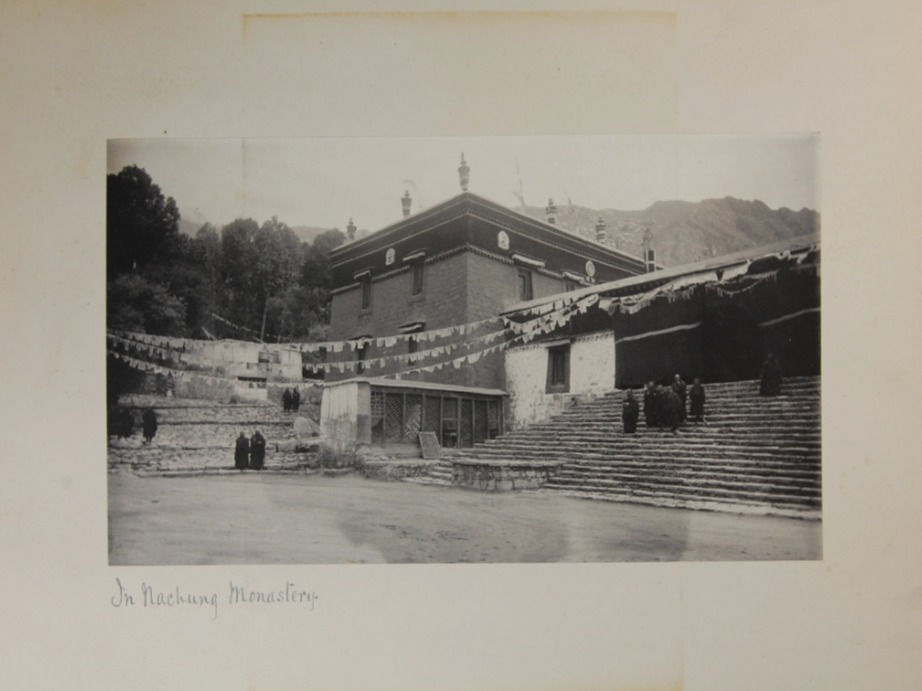

Figure 4.

“In Nachung Monastery”. Photograph by John Claude White, August 1904. From Lhasa Album in the Collection of National Museums Liverpool 50.31.148,

This image was taken by John Claude White during his expedition into Tibet. As the appointed, ‘Joint Commissioner' on the Mission to Tibet under Francis Younghusband.

Martin, Emma. 2020. “August 1904: Nechung Oracle’s Breastplate.” May 12, 2020, https://objectlessonsfromtibetblog.wordpress.com/2020/05/12/ august-1904-nechung-oracles-breastplate

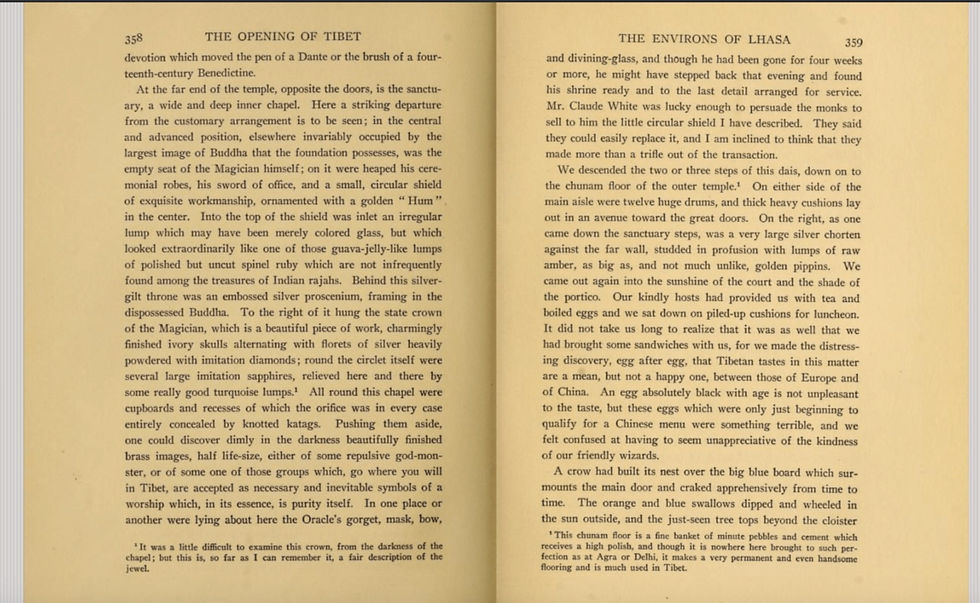

Figure 5.

The pages in Landon’s account describe the breastplate and the Nechung Monastery. From: Archive.org

In addition to John Claude White, Perceval Landon made note of his first visit to the Nechung Monastery and recounted the events. It’s here where the “retrieval” of the breastplate occurred after encountering the monks who were taking care of the monastery in the Nechung’s absence. Landon’s account of the monastery is an interesting reflection of monastic society, noting the mystical elements of the monastery with terms such as, “Magician”, and “Wizardry”. A likely perception of westerners contributing to the foreign nature of Tibetan Buddhism. The transaction in retrieving the breastplate is an additional reflection that sparks questions on the method of obtainment. It’s never recorded whether Claude White and Perceval Landon used force to retrieve the item, but rather the implication that the monks insisted on replacing the item is an opportune reason for why the expedition would have had it in the first place.

Martin, Emma. 2020. “August 1904: Nechung Oracle’s Breastplate.” May 12, 2020, https://objectlessonsfromtibetblog.wordpress.com/2020/05/12/ august-1904-nechung-oracles-breastplate

Figure 6.

The accession number as well as the original label for the item is dated above. As aforementioned, the accession number in museum objects is used as a method to keep track of items under the high volume of collections that institutions have. In collection theory, Jean Baudrillard references how meaning is defined and changed by a person based on who has contact with a given object or idea. The mislabeling of the Nechung’s breastplate to “Manchung Mon '' is a prime example of a shift in the object’s identification and meaning. This is a significant point of reference for the collection of Tibetan object’s throughout the Western world, as consumers of these artifacts, viewers must ascertain that each object in post-colonial spaces is subject to critical analysis.

Baudrillard, Jean. “Jean Baudrillard.” The System of Objects by Jean Baudrillard (400ES) - Atlas of Places, 2018. https://www.atlasofplaces.com/essays/the-system-of-objects/.

Martin, Emma. “Nechung Oracle Breastplate.” National Museums Liverpool. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/artifact/nechung-oracle-breastplate.

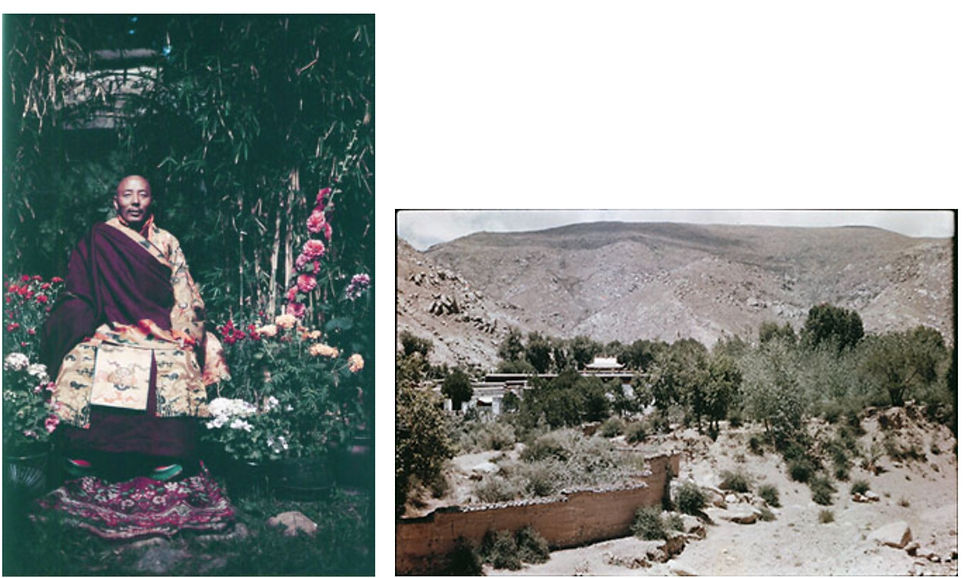

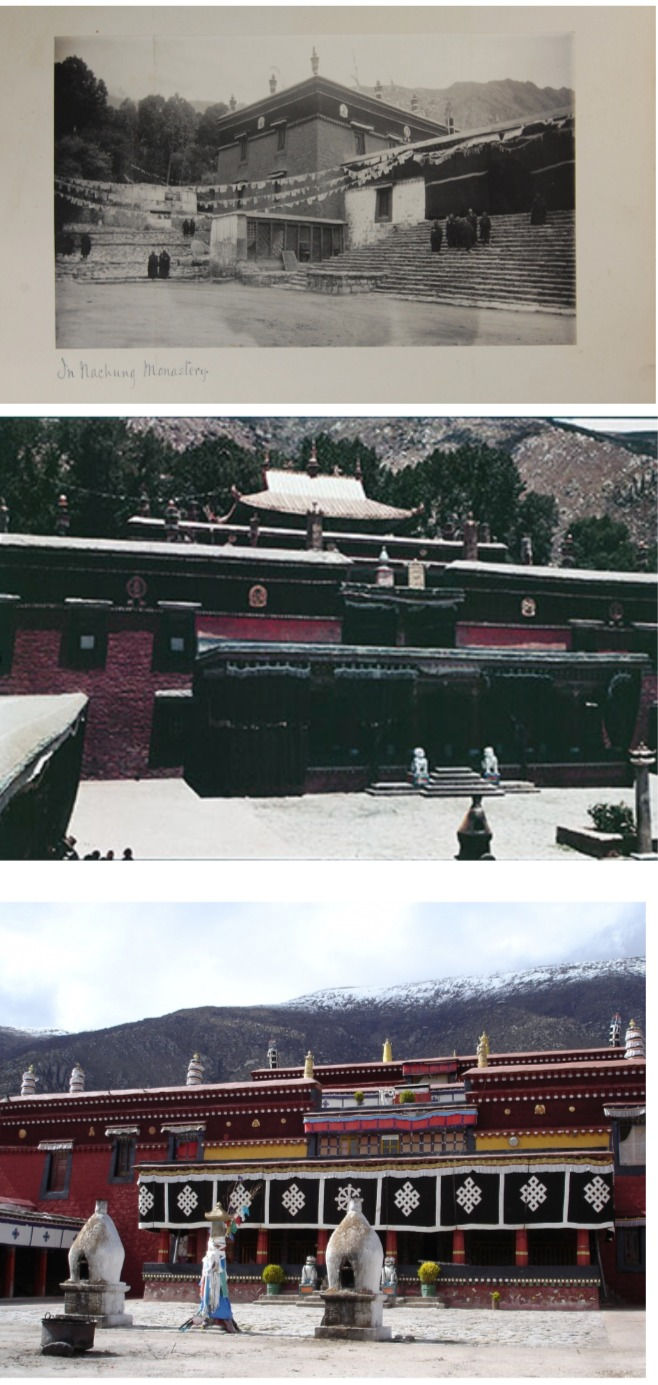

Figure 7. Figure 7.1

The image to the left was taken sometime between 1936-1950 by Hugh Richardson. The Venerable Lobsang Namgyal is seated on a bamboo grove in a garden with a carpet underneath. A common style of portrait photography for the elite or religious figures at the time.

The image to the left is of the Nechung Monastery sometime between 1936-37 captured by Frederick Spencer Chapman. Taking note of the geography at the time, the landscape was mostly surrounded by mountains and the natural push towards isolation functioned as protection for monastic institutions such as these.

The Tibet Album. "Nechung oracle, Lobsang Namgyal, at Nechung" 05 Dec. 2006. The British Museum. <http://tibet.prm.ox.ac.uk/photo_BMR.6.8.60.html>.For more information about photographic usage or to order prints, please visit The British Museum

The Tibet Album. "Nechung Monastery" 05 Dec. 2006. The Pitt Rivers Museum. <http://tibet.prm.ox.ac.uk/photo_1998.157.29.html>.For more information about photographic usage or to order prints, please visit The Pitt Rivers Museum

Figure 8.

As referenced in Figure 4, this is the Nechung Monastery captured by John Claude White in 1904.

Figure 8.1

This image is the Nechung Monastery captured between 19336-37 by Frederick Spencer Chapman. The front courtyard is photographed along with the surrounding environment.

The Tibet Album. "Courtyard of Nechung Temple" 05 Dec. 2006. The Pitt Rivers Museum. <http://tibet.prm.ox.ac.uk/photo_1998.157.39.html>.

Figure 8.2

This photograph was captured by Cecilia Haynes in 2011 and posted by the Rubin Museum for an exhibition on the Nechung Monastery. Contrasting the differences between its first photograph in 1904, 1936-37, and 2011, the architectural structure remains the same except for the addition of the front courtyard.

Haynes, Cecilia “Tour the Cosmic Realm of Nechung Monastery: Rubin Museum of Art.”The Rubin, December 16 2016.https://rubinmuseum.org/blog/cosmic-tour-of-nechung-monastery-palace-lhasa-tibetan-buddhist.

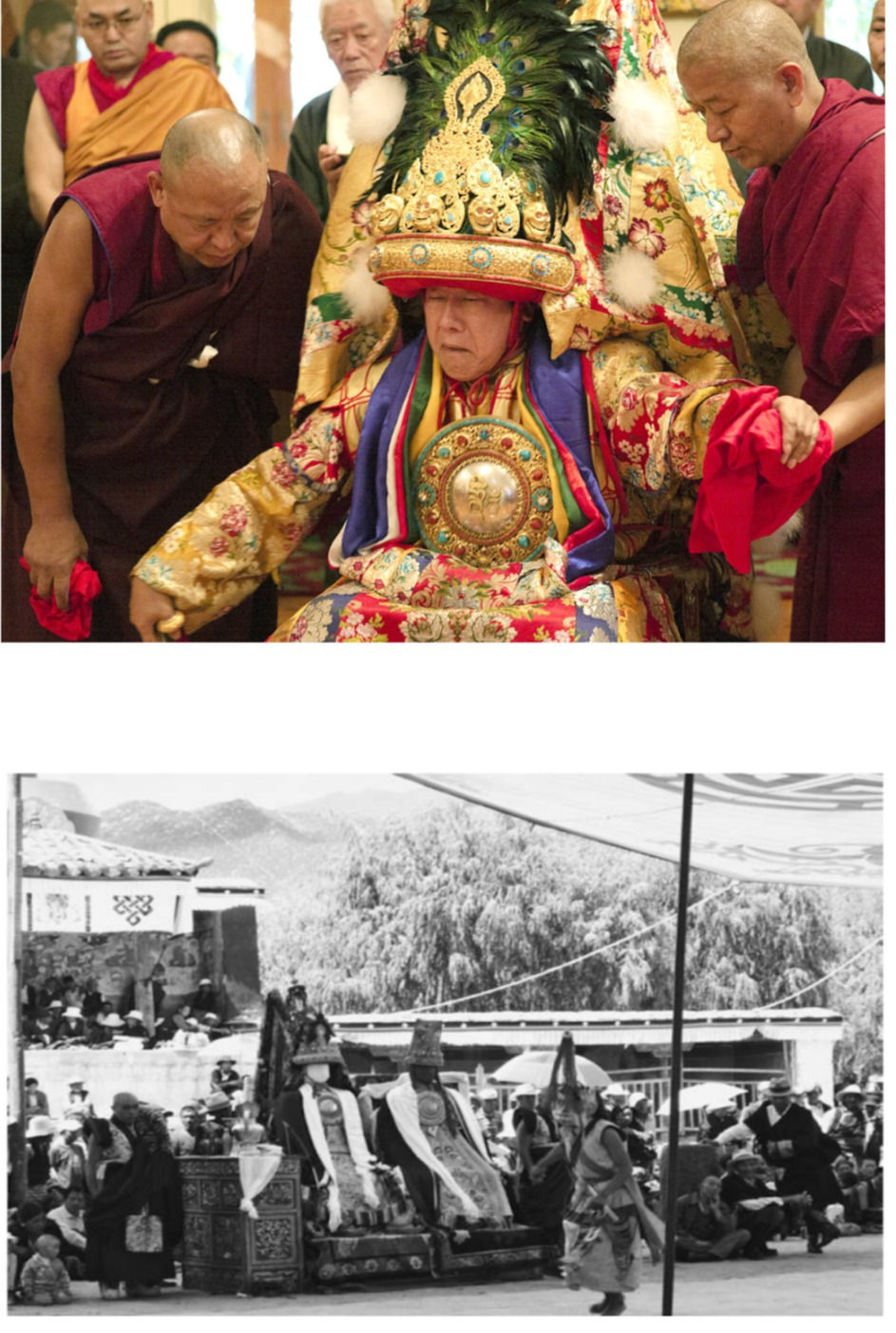

Figure 9. Figure 9.1 Figure 9.2

The figure to the far left is the depiction of Pehar, photographed by Christopher Bell. The mirror is seen illustrated on the chest of the deity, simple with no adornments. It is portrayed to have a neck piece as well as streamers that fall to the ground, similar to the created piece in Figure 1.

The middle figure is a depiction of a worldly protector, striking a similar appearance to the Pehar’s appearance in figure 9. This image is estimated to be created between the 1800-1899 in Mongolia. Painted against cotton with ground mineral pigment, this image is noted to be from the Gelug lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. Once again, the breastplate is seen to be in the middle of the deity, this time adorned with a gold outline of the mirror and the draped streamers below.

The far right image is of the same emanation, identical to figure 9.1 with the difference in style of painting. Figure 9.2 is a ground Textile image with hyper realistic influences spread throughout the painting. A date of creation is not known. Once again, the mirror in the center is portrayed with streamers that drape below in a slightly different style.

Bell, Christopher, The Dalai Lama and the Nechung Oracle (New York, 2021; online edn, Oxford Academic, 22 Apr. 2021), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197533352.001.0001, accessed 12 Nov. 2022

“Item: Worldly Protector (Buddhist).” Worldly Protector (Buddhist) (Himalayan Art). Accessed November 30, 2022. https://www.himalayanart.org/items/53081.

Figure 10.

The image is a modern picture captured by the Dalai Lama’s official website. As portrayed in the image, the Nechung’s breastplate appears with the same written inscription in the center. The adornment now contains larger pieces of turquoise and coral as well as an outline of stone.

“Tibetan Oracles.” The Dalai Lama: Leadership and the Power of Compassion. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://gingerchih.com/tibetan-oracles.

Figure 10.1

Taken by Christopher Bell in 2017, the image relays ritual dances performed in front of life-size effigies of Pehar and another deity at Samye Monastery. Once again coming back to the notion of absence and the power of attire in this context. In 1904, the absence of the Nechung was made up for by the royal robes left at the Nechung monastery, holding the same level of symbolism for the deity as if the Nechung were there. Here, the same reenactment of symbolic importance is upheld by the rituals that take place in the absence of the physical human body.

Bell, Christopher, The Dalai Lama and the Nechung Oracle (New York, 2021; online edn, Oxford Academic, 22 Apr. 2021), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197533352.001.0001, accessed 12 Nov. 2022

Figure 10.2

This image is the most recent picture posted by His Holiness’ instagram team. I was lucky to come across it while scrolling through social media.

The Nechung Oracle made an appearance for the November 30th long-life prayer at Dharamsala while wearing the Royal Regalia.

Choejor,Tenzin,Dalai Lama, “Photos of HHDL”. Instagram, November 30,2022,https://www.instagram.com/p/CllJrhGLyV2/

Bibliography

Baudrillard, Jean. “Jean Baudrillard.” The System of Objects by Jean Baudrillard (400ES) - Atlas of Places, 2018. https://www.atlasofplaces.com/essays/the-system-of-objects/.

Bell, Christopher, The Dalai Lama and the Nechung Oracle (New York, 2021; online edn, Oxford Academic, 22 Apr. 2021), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197533352.001.0001, accessed 12 Nov. 2022.

Choejor,Tenzin,Dalai Lama, “Photos of HHDL”. Instagram, November 30,2022,https://www.instagram.com/p/CllJrhGLyV2/

Columbia Tibetan Studies. “Mirror.” Columbia tibetan studies, July 23, 2019. https://blogs.cuit.columbia.edu/ajw2203/2019/07/23/mirror/.

Haynes, Cecilia “Tour the Cosmic Realm of Nechung Monastery: Rubin Museum of Art.”The Rubin, December 16, 2016.https://rubinmuseum.org/blog/cosmic-tour-of-nechung-monastery-palace-lhasa-tibetan-buddhist.

Martin, Emma. “Nechung Oracle Breastplate.” National Museums Liverpool. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/artifact/nechung-oracle-breastplate.

Martin, Emma. 2020. “August 1904: Nechung Oracle’s Breastplate.” May 12, 2020. https://objectlessonsfromtibetblog.wordpress.com/2020/05/12/august-1904-nechung-oracles-breastplate

Landon, Perceval,. The opening of Tibet. New York: Doubleday, Page & co, doi: 10.5479/sil.861467.39088017108721

Kapstein, Matthew T.. The Tibetans. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2006. Accessed November 29, 2022. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Wangyal, Phuntsog. “The Influence of Religion on Tibetan Politics.” The Tibet Journal 1, no. 1 (1975): 78–86. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43299785.

“Item: Worldly Protector (Buddhist).” Worldly Protector (Buddhist) (Himalayan Art). Accessed November 30, 2022. https://www.himalayanart.org/items/53081.

Study Buddhism, “Preparing to Go into a Trance| Ven. Thupten Ngodup, the Nechung Medium, 3:49, April 30, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lN3NmaWjIPM

The Tibet Album. "Nechung oracle, Lobsang Namgyal, at Nechung" 05 Dec. 2006. The British Museum. <http://tibet.prm.ox.ac.uk/photo_BMR.6.8.60.html>.

For more information about photographic usage or to order prints, please visit the The British Museum

The Tibet Album. "Courtyard of Nechung Temple" 05 Dec. 2006. The Pitt Rivers Museum. <http://tibet.prm.ox.ac.uk/photo_1998.157.39.html>.

The Tibet Album. "Nechung Monastery" 05 Dec. 2006. The Pitt Rivers Museum. <http://tibet.prm.ox.ac.uk/photo_1998.157.29.html>.

For more information about photographic usage or to order prints, please visit The Pitt Rivers Museum

“Tibetan Oracles.” The Dalai Lama: Leadership and the Power of Compassion. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://gingerchih.com/tibetan-oracles.

Comments