Women without Men

- Dolma Tenzing

- Mar 21, 2023

- 12 min read

Updated: Jun 28, 2023

The one whose hand is in fire is not like the one whose hand is in water.

Written in 2022

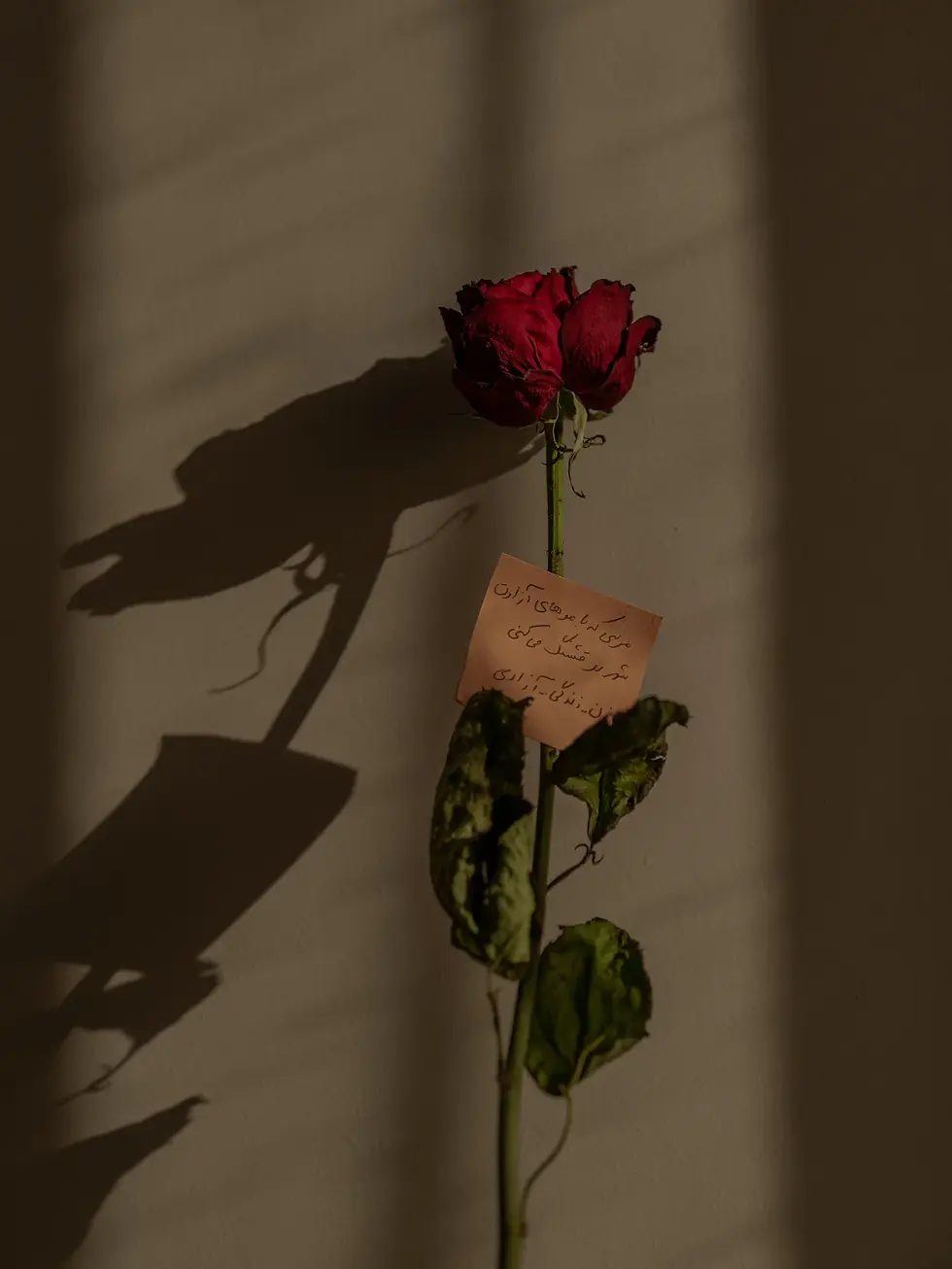

Mahsa Amini is the fire that lights so bright in the hearts of Iranians as people take to the streets to protest against a controlled state. Over the last decade, protests in Iran have been as valorous as seen in the 1979 revolution, echoing Iran's continual strive towards a balanced state. The young people from 1979 have since watched their country run under Khomeini and Khamenei's rule. Mahsa Amini was a living, breathing person. She was a daughter, a friend, but most of all, a woman with a heart and a mind. Amidst social media activism and the millions of shares, Sepideh Rashno, and Nika Shakarami (and many more) have become the epitome of this re-birthed revolution. As power and revelation began to shock the west, this was not the first protest of its kind. Iranian women have always served as a stronghold amidst the strict control over their autonomy. The issue of control and personal liberty for women within Iran is a deeply complex, politically embedded, and misunderstood part of Iran's history rooted in colonial history. In understanding, just one slice of the amalgamation, a deconstruction of history is necessary among critics of the Iranian state. How do we understand Iran's attitudes toward freedom without assuming a binary cause? How can we engage in dialogue about the lived experiences of revolutionaries in the present and keep their vision alive? How can we understand the term "Intersectional" and its power over a historically feminist regime that has redefined the sociopolitical role of Islam? These are all questions we should opt to explore by deconstructing the historical background of Iran.

In 1979, the Iranian Revolution lit a flame that burned so bright that it compelled the rest of the world to watch the shadows of a country deposing its monarchy, the Pahlavi dynasty. The revolution sparked a lamented nation whose livelihoods were cast over by the lingering impacts of imperialism, leading to a shift in Iran's foreign relations, civic restitution, and the socio-religious Ulama, which influenced political order. Various scholars attribute Iran's revolution to the discontent held with the Pahlavi dynasty, the exile of cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, and the steadfast modernization of the country. While the Shi'a country began to establish the Islamic republic after the return of Khomeini, a crucial aspect of the revolution remained untouched. The shadows of Iranian women and their influence on Iran's path towards a "perceived social justice" are often dismissed for their complex and pharisaical stance. However, Iranian women's roles were provoked by imperialism, which established class and rank that predated and outlived the revolution. As a result, the nascence of multifaceted feminism created a staggering effect on the collective liberation of men and, eminently, women in Iran. Some of these forms of feminism included a Liberal, Marxist, and Radical approach, which ultimately contributed to solidifying the current Islamic Republic. The complexity of social order and gendered precedent is masterfully illustrated in the adaptation of Shahrnush Parsipur's Women Without Men. In the film, viewers can explore the repercussions of imperialism that affected the lives of four women living in Tehran in 1953. The film utilizes magical realism through a historical lens to approach the complexity of Iran's socio-political relationship with women and how it would impact future revolutions.

Diving into the realm of the Iranian revolution and its impact on women requires a step back into pre-revolutionary causes. Under the Pahlavi dynasty, Iran was a powerful and centralized state that blossomed with rapid urbanization (Foundation, Encyclopedia Iranica). At the time, Iran held on to roughly four social strata of class: bureaucrats and western-influenced working professionals who boosted the bourgeoisie, the white-collar middle class, the working lower-middle-class, and finally, the rural class. Iran's proximity to Westernized ideals heavily influenced the establishment of the social class due to relations with the British and United States. Since its founding in 1909, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) created a massive rift in how foreign intervention regularly interceded with Iranian policy. Mohammad Reza rose to power during World War II after the forced abdication of Reza Shah Pahlavi. At this point, the relationship between Iran's royal family and foreign forces was tied as one, enforcing policies such as the Consortium Agreement of 1954 that allowed Western oil companies to hold a 50% share in Iranian oil production (Parvaz, "Iran Revolution" Al Jazeera,). This agreement only ignited the flames of the 1979 revolution as a broad backlash began to ensue, enlightening the masses to reclaim their country against Western intervention.

Twenty-Six years earlier, before the Iranian Revolution, during the 1953 Coup D'état, the first indication of a social uprising became apparent as the country was heading into conflict over the exile of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. At this time, a cycle of "arbitrary rule-chaos-arbitrary rule" in Iran was a common theme as the lines between dictatorship and democracy continuously changed (Katousian,2). In an attempt to create and extend a constitutional and democratic government, Mosaddeq and the Popular Movement uplifted a national identity, particularly centralized on the power of economic independence. As mentioned earlier, the APOC was a major player in the role of British and American influence over Iran's economic autonomy, leading Mosaddegh to push for Iran's repossession of oil operations. Various proposals were thrown to negotiate a policy that would still give Iran sovereignty; however, none remained acceptable. As a result, the CIA proposed the removal of Mosaddegh to restore an "arbitrary rule" through the "London Draft." With the help of the British M16, Mossadegh was exiled from office, placing the foreign-accustomed Pahlavi Dynasty in order.

The impact of these events can be viewed closely in the film Women Without Men, inspired by Shahrnush Parsipur's writing. Here, viewers see the rise and fall of female liberation during the coup by developing class systems that would later implode during the Iranian revolution.

Haideh Moghissi, in her piece, "Women, Modernization, and Revolution in Iran," expresses the diversity of Iranian women's social and experiential origins, citing three different groups. The first groups were broadly educated women of an emerging middle class who held communist and socialist tendencies and supported the revolution against the Shah, but not the clerics. These women wanted an end to Iran's foreign economic and political domination at the time. The second group was urban lower-class women who sought liberation through their clerical leaders. These leaders fell under Khomeini's leadership, who had promised a decrease in the price of electricity and water, creating opportunities for construction in the developed shantytowns surrounding Tehran. The final group was women in urban class settings, typically marked by traditional households. Women's roles enforced a fear and disdain for the modernization endowed by the Shah and his policies that followed. The women identified heavily with their men, who held deeply to their Islamic discourse. In this case, self-liberation was sought through the lens of the Islamic natural order, where gendered roles were essential to creating harmony. These were some of the clerics' most prominent supporters (Moghissi 207).

In the film, each character represented a part of these emerging classes, indicating how the next revolution would serve everyone differently.The first character, Munis, is a young woman who pushes heavily against her brother's wishes, Amir Khan, to be married. She continues to envelop the news on the radio spewing "Durood bar Mosaddegh, marg bar English" (Long live Mosaddegh, Death to Britain) until Amir threatens to break her legs. Instinctively, Munis is enthralled by the notion of revolution against the Shah, pushing for a communist agenda. She became a part of the underground Tudeh party that established the Women's League, later renamed the Organization of Democratic Women in 1949 and then the Organization of Progressive Women in 1951 (Sahimi Muhammad PBS). Dr. Mohammad Mosaddegh established a woman's right to vote in 1952 and was later granted social insurance by the Majles in 1953. Hence, political activism was one of the various ways women from this class chose to engage in social justice. Munis represent the roots of Haideh Moghissi's description of the emerging middle-class women seeking liberation from political repression. Although Moghissi dismisses any feminist partiality in this class, Munis demonstrates a Marxist-feminist approach that criticizes capitalism as a non-focal issue that assesses Iran's economic, political, and societal organization. Christine Di Stefano coins Marxist feminism as a political form of liberation keen on the debasement of freedom (Stefano 5). For Munis and other young, college-aged women at the time, freedom from the reigns of British rule meant personal liberation.

The storyline shifts to Faezeh; she functions as a transformational character, embodying the connection between each class in fighting against the impact of 20th-century imperialism. Faezeh begins her journey in the shoes of what Moghissi would describe as an urban class-setting woman; she is immensely pious and finds refuge in preserving her virginity. She admonishes Munis' desire to protest and advises that she stay at home. Faezeh wishes to marry Munis' brother, Amir Khan. Amir Khan is a representative symbol of the gendered devout male in Iran at the time, where neither the Shah nor Mosaddegh's plan seemed to appeal to them. Instead, Amir sticks to his religious conservatory and pushes this upon his family and those around him. In 1979, those who supported Khomeini's agenda included people similar to Amir Khan; this is an essential aspect of the changing revolution within Iran, especially when observing the significance of the 1979 revolution where various people and subgroups-specifically men- come from all walks of life.

In a piece titled "The Causes and Significance of the Iranian Revolution," Said Amir Arjomand states,

"… coalitions of classes and social groups carried out the revolution. The Iranian revolution was no exception. Despite its central importance, the clerical estate under Khomeini's leadership was only one of the social groups leftists' guerillas, Westernized bourgeoisie, and the traditional bourgeoisie of the bazaar." (51 Arjomand)

These social class complexities are one of the many reasons the women's movement during the revolution has been examined as contradictory because of the overarching gender limitations that preceded socio-political class structures. Amidst the use of men in the story, Faezeh begins to push out of her devoted mold after being raped by two men, leaving a perpetual impact on her self-perception. As she develops throughout the film, she begins to show signs of personal liberational feminism expressed through adopting a less modest form of dress, removing her Hijab, and, most importantly, denouncing Amir Khan by calling out his behavior. When he comes back to ask for her hand in marriage, along with his second wife, she vehemently calls Amir Khan's plans as his "…will make to make me a slave to his third wife.".

The next character is Zarin, who is a prostitute living in Tehran. She represents a unique perspective on the emergence of Iranian feminism during the coup. While her story remains along the sidelines, having little interaction with the occurring revolution, she offers insight into men's roles throughout the film. Zarin transcends various male-dominant spaces from the brothel to the Masjid and scowls at the sight of religious hypocrisy. She observes the men's behaviors in Tehran, serving to symbolize the women left in the shadows of protest and revolution. Her character also paints the systemic devaluation of women as just wives and mothers socially and legally empowered by the state.

The final character is Mrs. Farrokhlagha. A former wife of a general under the Shah, Mrs. Farrokhlaga holds a high standard of living among the Iranian social class; she opposes the gendered expectations that undermined the modernization movement under the Shah. Until the 1960s, the legal rights regarding family were primarily dictated by the Shi'a views when creating the first Iranian Civil Code in 1928 (Foundation, Encyclopedia Iranica). Throughout various articles, the outcome was that a woman's role in her marriage was to satisfy her husband. Any failure to do so could enable the taking of a second wife. This is directly referenced in Mrs. Farrokhlagha's experience when her husband states that he has the right to marry a second wife since she has been unable to satisfy his needs, eventually prompting her to claim dissolution and leave. Later on, in 1967, Iran adopted the Family Protection Act, passed under the Majlis. This act aimed to modify parts of the civil code, allowing legal guardianship of the children after the father's death and restricting polygamy and divorce. However, these reforms failed to recognize the social loopholes that invariably restricted the women's movement through 1979. Honor killings, restriction of employment, and financial support after divorce for the woman were still protected by the FPA (Hinchcliffe 520). Despite this "progressive move forward," introducing Sharia law eliminated the FPA after Shah's leave.

The film is immersed in magical realism, where the viewer is left to decide each woman's fate at the end of the film. Fortunately, for those who have observed Iran post-revolution, the movement toward female liberation has remained unyielding despite the challenges of the Islamic republic. An interesting observation in the women's movement lies in the changing feminist attitudes throughout time. As seen in the film, characters embody various forms of feminism. Today, we view how the revolution's short- and long-term impacts have enabled postmodern feminism to rise both within and outside of Iran. Several scholars have begun to coin "Iranian Feminism" as its realm of gender equality that shares thoughts on legal reform, specifically concerning Shari'a. Other forms of Iranian feminism also take a secular approach that favors human rights, civil governance, and democracy (Mahmoudi 15).

Iranians held great respect for the Ulama, and the transition from Shah's leave to Khomeini's leadership enabled a series of "Islamic revolutions" across the state and beyond. One of those revolutions included relations with Iraq. The Iran-Iraq war began in 1980 to maintain Iraq's Sunni-dominated Ba'athist leadership under Saddam Hussein (Sterner 209). For women at the time, particularly Middle-class families who supported the overthrow of the Shah, there was resistance to the sudden rise in Islamic fundamentalism that cast over Iran. In Marjane Satrapi's film "Persepolis," Marji's main character watches her social freedoms stripped away over time. There are scenes where older women are seen scolding Marji for her lack of modesty and settings where religious fundamentalism is placed in gender-separated schools. Despite these short-term aftermaths, we still see a correlation between characters like Munis and Marji, who remain believers in communism. Through generations apart, the long-lasting impact of each revolution has brought middle-class women to embrace a world that encapsulates political independence from the west and social liberties in freedom.

Forty-three years after the revolution, gender relations within Iran are shaping and shifting rapidly amongst the tensions between social moralities and legislative bodies. Myriads of men and women are growing out of traditional cultural ideals and regions, reaching for a society based on equality first. Civil disobedience is the nature of Iran's modern generations of grandmothers and great-grandmothers. Movements out of Iran, such as the Girls of Revolution Street and My Stealthy Freedom (as seen in figure 3), have served as platforms for women's gendered roles and regulations to be critically observed through a global lens. Iran is constantly under a shifting weight of foreign relations that directly and indirectly impact women throughout the state. Political activists such as Mahnaz Afkhami continue to challenge the Resurgence and New Iran Party. Journalists, including Mahboubeh Abbasgholizadeh and Maryam Amid, heavily influenced the feminist ideologies of the Quran and re-shaped Islamic feminism. Writers such as Shahrnush Parsipur and Marjane Satrapi offer routes to female liberation's creative and personal expression throughout time.

Iranian women have been the backbone of revolutions throughout time. By observing the intricacies of gender roles, social and religious order, and the repercussions of imperialism, complex relationships between political and personal liberation are seen throughout Iran's sustained history. These impacts result from an interwoven system of power that has continuously challenged and pushed the Iranian people to enact change within their socio-political system. This can be seen in Shahrnush Parsipur's work, "Women Without Men," with the complexity of gendered roles backed by an unsteady state of power. In 1979 during the Iranian Revolution, personal democracy led to today's Islamic Republic.

A good friend, colleague, and academic who introduced Shahrnush Parsipur's work to me shared a quote on the outlook of religious and political relations within Iran. She shared, "It is not about what Islam says; it is what Muslims do." (Wardah M.). As someone who exists outside of the realm of the Islamic faith and is analyzing an essential experience for thousands of Iranian women, it is evident across the board that it is personal. Each woman was an influential marker in Iran's makeup and post-revolutionary scene that flourishes today. Each step in a direction toward social reform within Iran could also signify a step back; Parsipur's film, "Women Without Men," challenges us to consider how one's liberations can exist simultaneously while also being challenged by class, patriarchy, and the remnants of imperialism. With the advent of social media and the time-space compression that occurs through our screens, it is easy to let our humanity dwindle with each swipe. While we consider the events occurring in the contemporary landscape of Iranian policy and the livelihoods of those tied to the land, let us use our words with an educated heart and open eyes as we turn to history being made today.

Sources are linked below for ways to keep up to date with Iran and movements that could use your support as well as citations for your interest.

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal, vol.40, no.4, 1988, pp. 519-531. The John Hopkins University Press, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3207893

Holden, Stephen. “In 1953 Iran, Sisterhood Sought during a Coup.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 13 May 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/14/movies/14women.html.

Scott, Joan W. “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis.” The American Historical Review, vol. 91, no. 5, 1986, pp. 1053–75. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1864376.

Talattof, Kamran. “BREAKING TABOOS in Iranian Women’s Literature.” World Literature Today, vol. 78, no. 3/4, Sept. 2004, pp. 43–46. EBSCOhost, doi:10.2307/40158499.

Vakil, Sanam. “Islamic Fundamentalism, Feminism, and Gender Inequality in Iran Under Khomeini (Book).” International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 36, no. 1, Feb. 2004, pp. 137–138. EBSCOhost,

doi:10.1017/S0020743804311074.

Comments