Embodied Cognitive Mysticism Exploring the the Nechung Oracle at the Center of Science and Religion (Chapter 1)

- Dolma Tenzing

- Jun 14, 2024

- 13 min read

Updated: Jun 16, 2024

This is Chapter 1 of a full thesis submitted under the guidance of Dr.Gray Tuttle from Columbia University.

A special thank you to my advisor, Dr. Gray Tuttle, Geshe Lobsang Nyandak, The Venerable Thubten Ngodup, Dr. Christopher Bell, Gyen Karma Ngodup and my Tibetan language instructors, Gyen Sonam Tsering (1 & 2), Gyen Lhun Kalsang, and all of my friends I made along the way while I traveled in Dharamsala. An additional thank you goes out to all of my professors at Columbia University who took interest in my work and continue to encourage me to push for my research.

I am especially thankful for my family who supported me.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction- Tibetan Oracles and the question of Consciousness ………….…..2

1.a.Pehar and the Nechung Oracle- Origins and Historical Contextualization……………........................4

2.b. Tibetan Cosmology: Deities ……………………………………………….………..............................................13

Chapter 2:

Exploring Tibetan Ritualism: Western Frameworks and Cultural Perspectives……….......15

2.a. Note on the Structure of Interviews and Data Collection…………………………....................................21

Chapter 3:

Tibetan Mediumship: Insights from Lineage, Lived Experience, and Philosophy ………....22

3.a.An Introduction to Key Terms………………………………………………………...............................................23

3.b.Patterns and Lineage in Mediumship……………………………………………….............................................24

3.c.Early Signs of Becoming a Medium………………………………………………..............................................…25

3.d.The Experience of Trance…………………………………………………………….................................................28

3.e.Making sense of Trance through the Abhidharma……………………………......................................……...32

Chapter 4:

Buddhism and Science: Approaches to Mediumship.……………………………………….......................35

4.a.The Science of Buddhist Traditions and Practices…………………………………...........................................36

4.b.The Tensions between Buddhism and Science……………………………………...........................................…46

Chapter 5: Conclusion……………………………………………………………………..........................................…….49

5.a.Considerations and Limitations……………………………………………….................................................………51

Appendix……………………………………………………………………………………….

Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………...................................................….55

We realize there is no such thing as an objective standpoint, and that the hardest enculturated worldviews to understand are our own, since we are embodied inside them and they are embodied inside us. - David Cave and Rebecca Sachs Norris

Chapter 1: Introduction- Tibetan Oracles and the question of Consciousness

A Tibetan deity predating the 6th century and the field of Neuroscience may seem worlds apart at first glance. Yet, a deeper dive reveals a surprising intersection between the two: the role of Tibetan Oracles in contemporary discussions on consciousness and cognition.

In academic circles, the concept of consciousness has ignited enduring debates, intertwining with some fundamental philosophical questions: What am I experiencing? Is this reality? What is my purpose? In recent work, the metacognitive approach has compelled scholars to confront the mind-body dilemma: What links the physical body to the mind?

Tibetan Buddhism offers a distinctive perspective on this question, offering insights that provide a three-dimensional view on consciousness. One such perspective emerges from the esoteric practices of Oracle work and mediumship, traditions that span centuries of Tibetan history and persist in today’s contemporary practices. Through the lens of mediumship, this research aims to explore three important questions: How do Oracles experience trance? What cognitive insights can be gleaned from understanding Oracle work? And what tensions exist between scientific inquiry and Tibetan Buddhist practices, thus shaping this research?

Focusing on the Nechung Oracle as a case study, this research navigates a diverse landscape, encompassing the historical context of the Nechung Oracle, its significance within the Tibetan community, methodological considerations in researching Tibetan practices, and the cognitive and scientific dimensions of Oracle work. Overall, it illuminates the tensions inherently embedded in these questions.

Drawing on interviews conducted in Dharamsala, India, this study bridges the experiences of the Nechung Oracle with the works of various theorists and neuroscientists who explore the interconnectedness of these seemingly disparate realms. Observing the Nechung Oracle through a multidimensional lens, this paper presents a new perspective on the role, function, and production of the Oracle’s practice and delves into intricate research methodologies concerning meditation and trance experiences. Hence, establishing connections with potential scientific applications in comprehending the Nechung Oracle during states of trance.

It should be noted that in this paper, I use the terms Oracle, Medium, and Kuten (sku rten) interchangeably when referring to the Nechung. Oracle work is typically classified as a shrine in which a deity reveals hidden knowledge or the divine purpose through a chosen individual. In the Tibetan context, the term Kuten refers to “bodily support, art and iconography, holder or receptacle of a person himself” based on the Tibetan to English translation tool. The Oracle himself is known as the Venerable Thubpten Ngodup, whom in this work is referred to as the Kuten la.

1.a.Pehar and the Nechung Oracle- Origins and Historical Contextualization

The Nechung Monastery in Lhasa, Tibet contains a mural depicting a powerful deity with a set of arms holding a sword and stick while brandishing a bow and arrow. The Vajra is held close to the deity’s heart while he stands mounted on a snow lion, marking the divine presence of protection through his three-fold face (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Image of Pehar at the Nechung Monastery, sourced from Christopher Bell

This mural is just one depiction of Pehar (Pe har) as his existence spans generations dedicated to the various forms and lives of Pehar as a spiritual entity. The origins of Pehar are multifaceted, stemming from a complex network of ontological roots interwoven with spiritual deities. These origins are detailed within Tibetan Buddhist literature but also extend beyond it. Pehar's emergence traces back to the reign of Tibetan King Trisong Detsen (755-c.797), where his presence and influence were first observed. Pehar’s role began to grow once His Holiness the Fifth Dalai Lama named Pehar as the primary protector of the Gelukpa school, marking his contemporary title as the Nechung Oracle (Gnas Chung).

Of the many oracles and deities that exist in the Tibetan Buddhist cosmology, the Nechung Oracle is an important figure that Rene de Nebesky-Wojkowitz classifies as a part of the chos skyong (Skt. dharmapāla, dvārapāla) or Dharma protector (See figure 2). Colloquially speaking, the Nechung Oracle is classified as a protector of the Buddha Dharma. To understand the role and function of the Nechung and its presiding deity–Pehar– it’s important to explore the origins of this Oracle.

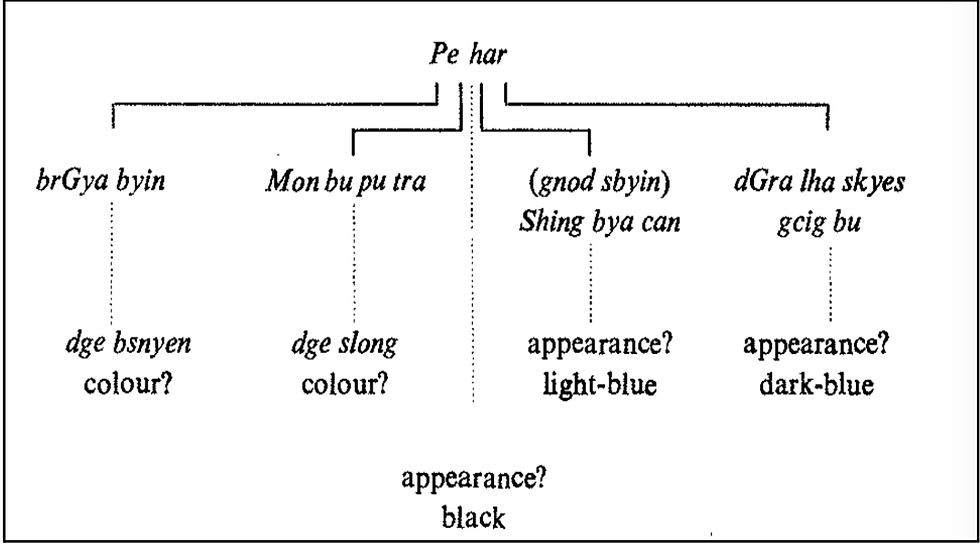

Figure 2.

Taken from the work of Rene De Nebesky-Wojkowitz highlighting the different appearances that Pehar takes on.

The quality of Pehar's essence is rooted heavily in his ability to hold many faces; consequently, the literature found within Tibetan sources cites various versions of Pehar, leading researchers and historians to explore the enigmatic nature of Pehar. During his establishment of power through Tibetan courts and the adoption of Buddhism, Trisong Detson's commitment to uplifting Buddhism was said to be hindered by the indigenous deities who resided on or in the land. These "wrathful indigenous deities and demons hostile to the foreign religion" were eventually defeated with the support of Padmasambhava (Padma' Byung-gnas), who conquered the spirits and instructed them to serve instead as newly ordained protectors of the Dharma. Padmasambhava's role in establishing these monastic sites, such as Samye, elevated the rise of esoteric Buddhism, which would later be contested in the 11th century by King Yeshé-ö. Pehar was among the deities who were conquered and was specifically appointed by Padmasambhava as a central guardian of Samye Monastery, upon its founding in 779 C. According to scholars Homayun Sidky and Robert Thurman, the origin story of Pehar in Padmasambhava's legends states that Pehar traveled with Padmasambhava from Central Asia, thereby establishing Pehar as a non-traditional Tibetan deity and emphasizing his multifold nature.

Pehar is often associated with inner Mongolia and the Bata Hor, however, the claims of Pehar originating as what would be classified in the modern sense as a Mongolian deityare not concrete. This foreign classification of Pehar's existence is further supported by the Nyingma (Rnying ma pa) classification of protectorate deities, where Pehar oversees the group of Sku Lnga (the five bodies). Figure 3 found in Nebesky’s work highlights the various “emanations” that comprise and connect to each of the sKu lnga. Based on these various emanations, the role and function of Pehar’s multifold appearance is believed to be in an effort to aid in dangers which could arise simultaneously in different parts of the country. Therefore, Pehar split himself into multiple emanations to which the significance of the number five appears. Nebesky-Wojkowitz's research places Pehar as a “lesser” deity in the traditional realm because of its status as a non-natural artifact of the Tibetan faith.

To the best of my knowledge, there is no single primary source that can conclusively substantiate Pehar's origins; however, multiple sources from the White Crystal Rosary root tantra, Tantra of the Capricious Spirit Norlha Nakpo, and the Black Iron Rosary Tantra are treasure texts which share variant narratives on the origin of Pehar, and are thought to be sourced from Padmasambhava.

Figure 3.

Chart based on the work of Nebesky-Wojkowitz outlining the broad classification of Tibetan Protective Deities.

The Fifth Dalai Lama used the White Crystal Rosary root tantra to indicate an origin tale for Pehar, noting that Vajrapāṅi is referenced as the subduer of Pehar due to his mischievous manner. The Tantra of the Capricious Spirit references Pehar's multiple past lives, utilizing key characters such as the Indian God Brahmā as the subduer of Pehar (rather than Vajrapāṅi). The final primary source is the Black Iron Rosary Tantra which shares the following,

Within the immeasurable palace of the gods and spirits, there dwelled together the leader of the capricious spirits, Vajrapāṅi, as well as Leiden Nakpo, the layman Norlha Nakpo, the eight classes of male and female barbaric spirits, [Norlha Nakpo's] hindering spirit consort Śanti Rozen, his mother Düza Minkar[ma], the seven siblings—Patra, Putra, shadröl, kyidröl, zinpo, dompo, and mönpa—Shiva, Vaiśravaṇa, Yamshü Marpo, Garwa Nakpo, the leader of the sky spirits, and the eight classes of gods and spirits.

This source identifies a relational value between Pehar and various other deities under the authority of Heruka (Khrag 'thung). Additionally this indicates another form of Pehar, as the layman Norlha Nakpo, further contributing to the multiple identities and lives that Pehar exists in throughout the Tibetan vernacular.

These sources illustrate the labyrinth of Pehar's identity starting as early as the eighth century. The transition to the tenth through twelfth century began to display the growing significance of Pehar in the view of Tantric practitioners, fundamentally altering the Tibetan Buddhist landscape as new forms of religious practice spread from the Western plateau.

In the eleventh century, a Buddhist revival began across Western Tibet under the king, Lha Lama Yeshé-ö (947-1024). Under Lang Darma (Uidumten (838-842)), a suppression in monastic Buddhism occurred throughout Central Tibet; however, communities towards Amdo continued to practice while in the West, the contributions of the Central Asia silk road upheld Buddhist practice. King Yeshé-ö was a firm believer in maintaining the Mahayana tradition by avoiding the dangers of tantric and esoteric practices that were taken literally. To press against the tantric practice, King Yeshé-ö released an ordinance stating,

Now, as the good karma of living beings is exhausted, and the law of the kings is impaired, False Doctrines called Dzokchen, 'Great Perfection,' are flourishing in Tibet. Their views are false and wrong. Heretical tantras, pretending to be Buddhist, are spread in Tibet'.

While King Yeshé-ö condemned these practices, he also promoted Rinchen Zangpo (Rin Chen bzang Po) (958-1055), otherwise known as the Great Translator, to spread and conserve Buddhist art and culture. In addition to his art and knowledge, Rinchen Zangpo was known to translate a series of tantric texts and shared a close experience with Pehar during his travels to Purang. Found in his biography, Rinchen Zangpo spotted a monk in meditation being worshiped by the locals. After examining the monk for some time, Rinchen Zangpo recognized the monk as the deity Pehar. Rinchen Zangpo left the monk in meditation and returned about a month later to point Pehar out. Once made known, Pehar released his human form, and the head of the monk fell to the ground, causing the entire body to disappear. Rinchen Zangpo's experience with Pehar as the misleading monk solidified the characterization of Pehar in the course of demonic and spiritual associations with deities at the time. Rinchen Zangpo's biography contributed to Pehar's gradual appearance in Tibetan literature and connection to popular beliefs during the 11th century.

Over time, tantric lineages continued to develop, and the Sakyapa and Kagyupa schools began to influence Tibet's political and religious history. These schools emphasized initiation and tantric instruction, which is seen in tandem with Pehar and the developing body of followers that grew during the 12th century. A prominent Buddhist movement influenced largely by the tantric initiation of Pehar occurred in the Dgongs-gcig Yig-cha, a collection of historical stories regarding teaching transmission. This text specifically references the Four Children of Pe-har, four prominent leaders active throughout the 11th-12th century in the Gstang and Phan-Yul provinces. These movements were also known as Rdol-Chaos, outbreak teachers. Of these four teachers, the first was Shel-mo Rgya-lcam. Shel-mo's husband was killed, and she suffered great grief; she turned to isolation and wept in a cave until Pekar (Pehar) appeared from the sky and said,

There is no connection between your thoughts and external objects; if there were since you cry and think about your husband, he ought to turn to you as before; you cried and called, but still, there is no husband.

Shel-mo Rygya-lcam was inspired by Pehar's words and thus adopted the teachings, “Thoughts and things have no connection. The very idea must be rejected by the teacher, student and teaching three, that they are the least bit interconnected”. Over time, Shel-mo gained a following and later sanctified the cave of her enlightenment as the Prophecy relic cave. The second teacher was Zhang-mo Rgua-’thing. During a religious exercise, Zhang-mo observed a bird kill a snake, at which point a leaf fell from a tree and made contact with the snake's corpse, which then disappeared. In this form, the bird was Pehar, leading Zhang-mo to adopt the teachings of nonexistence in nature. Her teachings are as follows, “I know that thinking the killer and killed suffer any effect is just a mistake, like a leaf, the bird and the snake.” This is not the first time Pehar has been recorded to share a relationship with birds and their forms. In a later text known as The Testament of Ba (Sba bzhed), Pehar is referred to as Shingjachen, which can be roughly translated to “He who Possesses a Wooden Bird.”

The final two teachers were 'O-lam Bha ru and Bso Kha-’tham. The view of these practitioners focuses on the actualization of self through the acceptance of killing. Both seemed to have adopted a notion of death and killing as lacking virtue and sin.

The experiences of the 'Four Children of Pehar,' as described above, demonstrate that Pehar's teachings were generally understood to be associated with invoking dark magic or the spiritual character of the tantric practices. Nevertheless, these character stories relay the influence that popular religious movements could gain during this period in Tibet. Historian Dan Martin makes a clear reference to the importance of perspective when analyzing the impact of Pehar, noting that these stories of the Four Children of Pehar were a radical account of a non-Buddhist approach to life at the time; therefore, its validity remains open to interpretation.

Pehar's background is a vast and complex web of ontological origins concerning spiritual deities both within and external to Tibetan Buddhist literature. In order to understand the transformations of Pehar into its modern-day role as the Nechung Oracle, the history of Pehar and his relationship with the Tibetan state and its developing lineages remains central to understanding the shifting power of religion and power. Later during the 15th century, Pehar became a ritualized part of the Tibetan governing body once His Holiness the 5th Dalai Lama began to work with the spiritual deity in his personal and political affairs. However, the importance of Pehar before his formal role, allows us to contextualize the origins and beginnings of Buddhist cosmological organization when it comes to Pehar and the Nechung Oracle.

Based on the accounts provided by the Nechung Kashag, the earliest documented relationship between any Dalai Lama and the oracle traces back to the era of the Second Dalai Lama, Gendun Gyatso (dGe’ dum n rgya mtsho) (1475-1542). Sparse textual references indicate occasional invitations extended to the deity during this period. However, it was the compositions of the Fifth Dalai Lama in the Nechung rites that solidified the oracle's historical significance and its strong connection to the Dalai Lama lineage.

In popular belief, the origin story of Nechung's residency in Lhasa recounts his installation at Samye Monastery, following an oath-bound convocation conducted by Padmasambhava to safeguard Buddhism. Nevertheless, historian Christopher Bell, in his chapter titled "Nechung Monastery," highlights discrepancies in historical accounts regarding Pehar's arrival at the Nechung Monastery. These contradictions may have arisen from the Second Dalai Lama's efforts to reinforce the historical link between the deity and the Dalai Lama lineage.

Over time, the role of the Nechung Oracle became increasingly intertwined with Tibetan political affairs as the influence of the Dalai Lamas grew. Following the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1949, the former Nechung Oracle accompanied the Dalai Lama into exile, where the current Oracle continues to reside. One of the major contemporary functions of the Oracle includes assistance in political affairs and more well-known, the Oracle's Work of aiding searches for reincarnations of the Dalai Lamas.

In contemporary times, the Nechung Oracle plays a significant role in ordained rituals, often at the behest of governmental authorities, shaping daily life in the exile community. While Pehar remains central among the Five King Spirits, Dorje Drakden, the protector deity, manifests through the Oracle today. This dynamic highlights the intricate relationship between these deities within Tibetan cosmology, adding layers of complexity to the ritual of trance.

2.b. Tibetan Cosmology: Deities

An important part of situating this research in the conversation of Tibetan deities and mediumship refers to the cosmological framework in which these deities exist. This section uses Réne de Nebesky-Wojkowitz’s ontological organization from his book titled, “Oracles and Demons of Tibet: The Cult and Iconography of the Tibetan Protective Deities'' to aid in understanding this complex format. Figure 2 provides an organized layout based on Nebesky-Wojkowitz’s work to elucidate the distinct organization of deities that will be discussed below.

Within Tibetan cosmology, diverse realms house deities and living beings. The upper realm, soaring above the earth like celestial spheres, hosts divine entities, known as “lha,” alongside esteemed beings. Among them, the highest-ranking are those rooted in Buddhism, serving as custodians of Buddhist principles and teachings, referred to as “dharmaptila,” “chos skyong,” or “bstan srung ma.”Additionally, “those bound by oath” (or “dam can”), originally non-Buddhist deities, were compelled to safeguard Buddhism upon its introduction to Tibet between the eight and eleventh centuries. According to scholarly classifications, the highest Buddhist protectors transcend the worldly realm (“’jig rten las 'das pa'i srung ma”). While Tantric deities also hold superior status, they are categorized differently.

In the realm where humanity dwells, it coexists with a myriad of supernatural entities, among them the “red demons” (referred to as “btsan”) and many others. Serving as guardians of the terrestrial realm (“jig rten pa'i srung ma”), these beings encompass local deities associated with geographical features, like mountains and lakes. Regarded as lower-level protectors, these deities pose potential hazards and necessitate management by Buddhist authorities. Some are specific to particular regions and may be focal points of regional cults, often manifesting through mediums. Hildegard Diemberger makes a distinction between a category of Oracles known as the ‘lhaka;(lha-bka’), ‘lhabab’(lha-’bab)m and the ‘lhaba’ (lha-ba) and or the ‘pawo’(dpa’-bo) and ‘pam’(dpa’mo). These deities classify themselves as strictly local Oracles who are distinct from the institutionalized oracles known as the ‘kuten’(sku-rten) like the Nechung.

The third realm, lying beneath the earth's surface, has serpent-spirits ("klu"), who are linked to the natural landscape and especially water. These local deities transition into malevolent spirits which can be one method of attaining illness. The term “lha” encompasses all deity types, including gods of the Buddhist heavens, tantric deities, and local deities. The distinction between local deities and demons can be blurred, adding complexity to categorization, especially in lay beliefs. Buddhist scholars have attempted to systematize this complexity by delineating three levels of subtlety and six spheres of rebirth, while also distinguishing between otherworldly and worldly deities.

As a result, the Tibetan pantheon comprises a hierarchical array of deities and supernatural beings, both malevolent and benevolent. The belief in communication between humans and entities across these realms is widespread, with Oracles consulted for various purposes such as weather forecasting, harvest prediction, identifying high reincarnations, illness diagnosis, divination, and offering gratitude.

For the Oracle himself and the many who preceded him, being intertwined with deities and the larger Tibetan cosmological world has presented an interesting opportunity to explore this relationship. Aided by the social and political reverence within Tibetan society, as Nebesky-Wojkowitz shares,

“Though he is in theory only the mouthpiece of the chief ‘jig rten pa’i sprung ma and some of its emanations, the oracle priest is nevertheless held in a high degree responsible for his prophetic utterances.”

The Nechung Oracle’s existence is an opportunity to view the complexities and frameworks of research which aims to view ritual and religious experience in an ontological way.

Comments