Exploring Tibetan Ritualism: Western Frameworks and Cultural Perspectives (Chapter 2)

- Dolma Tenzing

- Jun 14, 2024

- 9 min read

Chapter 2: Exploring Tibetan Ritualism, Western Frameworks and Cultural Perspectives

The academic exploration of Tibetan culture, religion, language, and history, began to capture the interest of Western scholars in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This period marked a significant turning point in Western engagement with Tibet and its rich cultural heritage particularly in the exploration and expansion of the Younghusband expedition in 1903. Since then, the study of Tibetan culture and history has been dominated in the West and has produced a series of frameworks which both contribute to and impact the narrative of aspects such as Tibetan ritual and practice. In her book “The Hammer and the Flute: Women, Power, and Spirit Possession,” Mary Keller delves into the topic of possessed bodies examined in the West, showcasing them through the lens of cultural agency in society. In her work, she presents a notable statement, expressing:

"Possessed bodies are markedly different from the contemporary Western model of proper subjectivity. They are volatile bodies that attract the eye of observers, and often their volatility is related to erotic or outrageous activity. Possessed bodies are not individual entities; rather, they are vessels through which an ancestor, deity, or spirit asserts influence. However, interpreting this phenomenon poses a challenge, as it may be difficult if not impossible for most scholars to represent as the 'truth' of the matter. By and large, scholarly approaches to possessed bodies have reinterpreted them as repressed psychological entities, oppressed sociological constructs, or manifestations of women's oppression."

Something intriguing about Keller's post-colonial theories on bodies briefly intertwines with the notions of the Tibetan body in contextualizing how mediumship and Oracle work are imbued in states of trance as embodied ritual practices. Moreover, how this informs scientific and historical researchers adds another layer to understanding of consciousness within the Tibetan context.

In this research, I draw upon frameworks and methodologies introduced and discussed by Kim Knott, Geoff Childs, and Toni Huber to illustrate how perspectives on Tibetan ritual, particularly those related to mediumship and trance states, are perceived and must be acknowledged within the realm of Western theoretical structures. This approach aims to recognize these cultural perspectives when examining the Nechung Oracle and its contemporary practices which are showcased during ritual trance. The following section draws on these different approaches and attempts to connect it to a Tibetan framework on Oracle work.

Frameworks by Kim Knott, Geoffrey Childs and Toni Huber provide researchers an opportunity to shed light on the concept of Tibetan ritualism and challenge Western ideologies that often influence perceptions of the practice. In Kim Knott’s work, The Location of Religion: A Spatial Analysis, and a collective journal titled, In Religion and the Body: Modern Science and the Construction of Religious Meaning, the conception of sacred space is moderated by the individual’s relationship to the environment. Kim Knott aims to develop a spatial methodology to examine religion in Western modernity, where the modern and postmodern perception of space is observed through a religious lens.

“My aims in terms of the theory of space, place, and location are threefold: to reflect upon space as a medium in which religion is situated; to develop a spatial strategy for examining the relationship between religions and its secular context; and to consider the spaces produced by religions, religious groups, and individuals in contemporary Western Societies”

Kim Knott adopts a relatively centrist view in her analysis of Sacred Spaces, understanding how space is neither an extreme limb of religion nor secularism but rather a space formulated by the individual’s own experience in religion influenced by a modern secular world. In chapter two of her book, Knott introduces Lefebvre’s Three Aspects of Social Space. The first section is the “Representations of Space”, which are conceived and conceptualized spaces that consist of dominant, theoretical, often technical representations of lived space conceived and constructed by planners, architects, engineers, and scientists of all kinds. Within this capital, spaces are embedded notions and perceptions of ideology, knowledge, and power. The second section “Spaces of Representation”, defines spaces represented as lived spaces against perceived spaces. The example Knott uses is Medieval life, where graveyards hold some cosmological purpose or practice, but it's inherently through the local customs surrounding the society that emphasizes its role. The final section is “Spatial Practice” where spaces are constructed from how people generate, use, and perceive space from a reproduction of action over time. Spatial Practice finds that “it structures all aspects of daily life and urban living, from minute, repeated gestures to the rehearsed journeys from home to work to play.”

Knott’s introduction to these spatial integrations by Lefebvre highlights the relevance and value that each aspect has to exploring one’s relationship and perception of sacred spaces. Examining external instances of religious space, we can observe how the representation of space directly influences social and cultural environments. For example, neo-Gothic architecture, influenced by the dominance of Roman Catholic spaces, serves as a notable representation of this phenomenon. Based on this, the religious conception of space had authority at the time which was translated across centuries into modern day churches and cathedrals. Eventually, with the help of industrialization and the power dynamic of politics, capital creation of these religious designs flourished under “Neo-Gothic” styles of built space. This framework offers insight into the co-development of Tibetan practices, notably the roles of Oracles and Mediums, within a contemporary Tibetan society. Historically, the swift institutionalization of the Nechung Oracle by the Tibetan political structure since the 17th century, alongside the integration of Tibetan cosmology and deities, provides a unique perspective on the evolution of Oracle work and its function in bridging religion and daily life within politics. As we delve into ritual practices and explore consciousness, Kim Knott encourages researchers to examine how cultural practices influence both physical and mental spaces, with distinct customs and traditions shaping individuals' perceptions of lived and perceived spaces. This research particularly focuses on how Tibetan ritualism impacts consciousness perception.

One historical example illustrating this influenced perception is the case of the Nechung Oracle. In this context, the Nechung Monastery engages in ritual practices in the absence of the Oracle, yet with the presence of its relics (figure 4). Consequently, the space becomes a sanctified ritual site, elevated by the active participation of monks, laypeople, and non-human entities. Even in the Oracle's absence, the collective consciousness of the deity endures within the space through these ritual practices, blurring the distinction between the physical body of the oracle and its relics. This underscores the sacred potential of both elements, contingent upon the appropriate rituals.

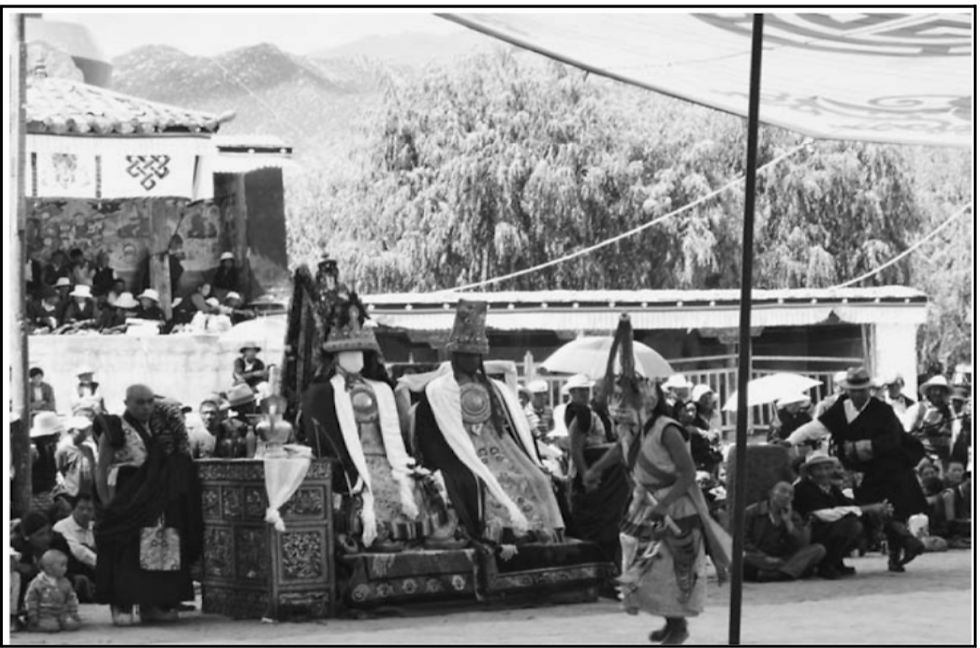

Figure 4.

Taken by Christopher Bell in 2017, the image relays ritual dances performed in front of life-size effigies of Pehar and another deity at Samye Monastery. Once again coming back to the notion of absence and the power of attire in this context. In 1904, the absence of the Nechung was made up for by the royal robes left at the Nechung monastery, holding the same level of symbolism for the deity as if the Nechung were there. Here, the same reenactment of symbolic importance is upheld by the rituals that take place in the absence of the physical human body.

During an expedition led by joint commissioners John Claude White and Perceval Landon, the Nechung Oracle's breastplate was removed from the Nechung Monastery during the era of the Younghusband British expeditions. Recorded by Perceval Landon between 1904 and 1908, this event coincided with the absence of the Nechung Oracle when the 13th Dalai Lama sought refuge in Mongolia. Despite the Oracle's physical absence, the Nechung Monastery persisted in its daily rituals, preserving its ornamental relics. This demonstrates the resilience of ritual practices and the enduring sanctity of sacred spaces, even in the absence of key figures.

Lastly, Lefebvre's concept of spatial practice interprets how daily life and communal living contribute to the construction of spatial competence. In Tibetan Buddhism, the embodied form of daily life differs between laypeople and monastic institutions. However, both communities share spatial practices influenced by deities such as the Nechung Oracle. In gatherings within a singular space, the observation of the Nechung in trance dictates specific behaviors and practices, shaping the Tibetan community's spatial interactions and competency.

Another important reference point, akin to Kim Knott’s ideas on spatiality, involves the concept of embodied space. Broadly speaking, we can draw from Kim Knott's work and examine how religious studies scholar Toni Huber and cultural anthropologist Geoff Childs approach Tibetan societal practices.The theory of embodied spiritual and ritual practice represents a vast and deeply complex understanding that Tibetans actively engage with as practitioners. Therefore, Toni Huber emphasizes the significance of emic and etic distinctions within Tibetan studies when analyzing theories in practice. The ability to observe from within or externally to the community significantly influences behavioral patterns or personal rationales. For instance, in this research, which broadly explores the relationship between scientific inquiry and religious experience, the etic approach tends to adopt a reductionist viewpoint from a scientific perspective regarding the experience of trance states.

One example of this phenomenon can be found in the work of Louis Child, who observes how various Durkheimian social theories incorporate Jungian psychology to analyze Tibetan tantric rituals. She explains that,

“It is possible to explore that aspect without reducing the entirety of the tantric Buddhist philosophy. Ritual and biographical material to a series of material or psychological problems expressing themselves through religion…altered states are not simply isolated phenomena that only have an impact on the agency of the person concerned. They are, to some extent, framed and interpreted by the surrounding community”

Where the etic and emic approach meet in Child’s work can be seen in the way she communicates states of trance as a collective experience. She makes one more reference to Mircea Eliade’s own work on religion and space where he uses the contact between the person in trance and the community as a way to push against scientific tendencies to reduce the experience to that of mental illness or deviant social behavior. Rather offering a very rich view on indigenous theoretical frameworks on the mind that introduce conscious agency. Something that is often missed in the Western scientific paradigm of religious experience.

In a similar attempt, Geoff Childs's “Methods, Meanings, and Representations in the study of Past Tibetan Societies,” Childs makes similar distinctions between research approaches. For Geoff Child, the importance of reliability and validity are cardinal to understanding past Tibetan societies. While a particular group or subject matter may express a reliable opinion shared by most people, its validity may be weak due to the expression of a common cultural form. Similar to Huber's work, researchers observing modern Tibetan society may perceive the Gnas-Kor as a Buddhist practice but may also omit its role as a Tibetan practice. Huber references this early on by stating,

"Privileging Indic doctrinal explanations for what Tibetans do and say has drawn the analytical focus away from a closer investigation of the assumed emic categories, such as 'place/space/'person' and 'substance,' and the qualities assigned to them, which Tibetans work with and even make explicit in a whole range of ritual scenarios. The result has been that both implicit Tibetan understandings of the world and the embodied ritual experience of Tibetan pilgrims have been largely overlooked, as have their social significance."

One noteworthy approach employed by Child to ensure the accuracy of research measures involves using structuralism and agency as tools for conducting person-centered interviews, where the informant and the respondent are one and the same. In my own research endeavors, conducted during my time in Dharamsala, I engaged in a variety of interviews applying Child’s methodology, particularly during interviews with the Nechung Oracle. As previously discussed, the application and influence of language in this research methodology were deeply rooted in the philosophical underpinnings of the Tibetan language, especially evident during interviews with teachers and the Oracle himself

2.a.Note on the Structure of Interviews and Data Collection

During my interviews, I collaborated with Gen Tenzin Tselpa in a group interview setting, alongside Geshe Lobsang Nyandak and the current Nechung Oracle, Venerable Thubten Ngodup. Gen Tenzin Tselpa served as a third-party translator in Tibetan, aiding in translating complex scientific terminologies I presented. However, the structure of these interviews was intentionally designed to provide agency to both parties involved. As a native speaker of a Tibetan dialect, I received information in both Tibetan and English, allowing me to discern terms that might be lost in translation or framed differently in English. Figure 5 illustrates the interview process in detail. With a focus on the Analysis of the mere ‘I’ (or self) designated independence upon the subtle wind-mind factor, Geshe Lobsang Nyandak completed his PhD from Bangalore University under the Dalai Lama Institute for Higher Education. As the chief editor of the Collected Works of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Lobsang Nyandak brings a wealth of knowledge to this research as his expertise and background aided in my curiosity about the philosophical approaches to understanding how Tibetan Buddhism conceptualizes the body.

Figure 5.

During my fieldwork in the Tibetan Exile community in India, I created a general chart outlining the interview process. Communication between myself (the interviewer), the translator, and the respondent was multimodal, involving both English and Tibetan to ensure comprehensive translation of terms not commonly found or used in the Tibetan language. The purpose of charting this process is to demonstrate how information from interviews was received and processed in this study.

Comments